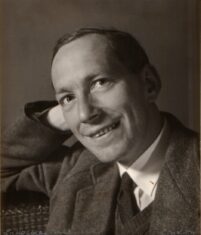

Kenneth Hutton, 1956, age 38

A frank and fairly short autobiographical/historical talk given in 1981 to the 6th Form by Kenneth Hutton, the first headmaster of Hatfield School, fifteen years after he left.

This original text was kindly provided by Kenneth’s family, and published on their behalf by Chris Hepden, who is responsible for any notes added.

One of the most disgraceful things I ever did as Headmaster of Hatfield School was to keep for myself the tear-off calendar which was sent each year to the Woodwork Department of the school by the woodworking firm of Fitchett and Woolacott. Each day of the year there was some thought-provoking saying, like that of the American poet Robert Frost :-

“If you work hard and honestly for 40 hours a week for 50 weeks of the year you’ll become Boss and work hard and honestly for 60 hours a week for 52 weeks in the year.”

That particular year, 1959, I think I had been working more like 90 hours per week! We had completed a year with our first lower-sixth form and we had completed the filter plant for our home-made swimming pool. So I fixed up a family holiday for 3 whole weeks, told my parents – and ONLY my parents – our address, and told my devoted secretary that if the end of the world happened she could write to my parents [in Newcastle] and thus get in touch with me. But, as she honestly did not know where I was, she was not being asked to tell lies by saying she didn’t know. It was a wonderful holiday in one of the sunniest summers for years, after which Harold Macmillan won the general election for the Tories by saying “You’ve never had it so good!” – or words to that effect.

When I came back, wonderfully refreshed from Tenby in South Wales, where we had played on the sands, learned a lot about Geology and I’d swum a mile in the sea, I found that there had been an almighty row in the press, and television, and “Christian Science” in the USA, about an indiscreet remark made in a pub by a teacher (one of my staff) about ‘improving pupil’s accents by ridicule’. But it had all blown over by the time I returned and I was feeling perfectly fit enough to pick up the pieces. Nowadays, 21 years later, I would have found it much harder both to relax so thoroughly and afterwards to pick up the pieces.

On the door of our kitchen we have pinned up one of those charming tea towels with the “RULES of my KYTCHEN”. The rule I like best is number 6 “DON’T CRITICIZE the coffee, you may be olde and weak yourself someday”. That’s what I feel like only too often, especially first thing in the morning. So how on earth was it that I was given the chance of a lifetime on 9th January 1953 when I was appointed as the first head of a brand new school, not yet built, under the most progressive of all the Education Authorities in the whole country?

Well, of course, I was younger then, 34 years old, and – especially – I was extraordinarily lucky. I have almost always been lucky. Even though my Mother died of cancer when I was 13, fortunately I had a splendid stepmother by the time I was 15, and home was a happy place, not just the home of 3 quarrelsome males! (My Father, my brother and myself) A teacher has to remember the absolutely fundamental influence of the home – the values and attitudes which are inculcated, whether you feel cared for and valued for what you are, and also of course the genetic endowment which you get from your parents. From my Mother I clearly got my love for music as well as a modicum of talent. I still have on my shelves the booklets of Opera Librettos published by the British Broadcasting Company (i.e. before 1926 when it became the Corporation – the present BBC), whilst my maternal grandfather’s oboe (which he gave up at the age of 80 when he got false teeth) is still played by one of my sons. In our sitting room is the Bechstein grand piano which my Father gave to my Mother in 1927. It is slightly faded because my parents – like me – were sun-worshippers and refused to draw the curtains to protect the furniture, but valued every scrap of sunshine which penetrated the soot-laden atmosphere of Newcastle-on-Tyne, my home town.

To be absolutely honest, I don’t remember much about my Mother except that she regularly used to practice the piano- and indeed had lessons – in order that she could help and encourage my elder brother and myself. In those days gramophone record were not up to today’s high quality and cost over 10 times as much. ( Beethoven’s Eroica Symphony, which I was given for Christmas when I was 15, cost 216 Mars bars; today you can get an excellent disc of it for £2.00 or 15 Mars bars – 15 instead of 216, and the quality is much better, and the records are unbreakable, lightweight, and play for 5 or 6 times as long before turning over) So, if you wanted music in those far-off days of the 1920’s you made it yourself. Mother on the Piano, brother on the violin, me on the flageolet (before I inherited the Oboe) and Father on the Cello (on which he had lessons at the age of 45 never having played an instrument before, in order to join in with us).

My Father was a rather terrifying man – we had to call him ‘Sir’. When I was your age (17 or so) I thought that everything he believed in was wrong, and that I was as different from him as I possibly could be. He was 1metre 90 tall (6’2”) whereas I was never more than 1metre 80 before I started to shrink; thin as a rake, he wore a bowler hat, was a churchwarden for 5 years and read the Daily Mail till he changed to the Daily Telegraph. But, after I had fought my essential battle that the younger generation always has to fight for independence of thought, we respected and understood each other and I found that my fundamental values were the same as his; reliability, honesty, hard work, generosity and not valuing a man by the size of his income or his car. A shy man, he knew that a good wife was worth more than 10 good friends, and 10 good friends more than 100 friendly acquaintances.

Physically, my Father had a weak heart, and had heart trouble at the age of 56, but was determined to prove the doctors wrong and lived happily till 79. My elder brother was less lucky; he had 2 heart attacks before he was due to retire at 60, and died of them. Guess what? I had heart trouble at aged 58 and am going to try to emulate my Father rather than my brother. [He actually made it to his heart attack at age 69]

Anyway, my parents believed in cod-liver oil and in education. That was very soon after the discovery of Vitamin D and, when I was young, bandy-legged children suffering from rickets were common. Not till the second world war was the addition of Vitamin D to margarine made compulsory and even the day that I write this it is estimated that up to half the Asian population in this country may be suffering from lack of vitamin D because of the lack of sunshine and a different diet suited to the sunny countries they came from.

There is a present-day heresy that there is no such thing as heredity – everything is caused by environment. “It doesn’t matter who your parents are, it is your surroundings that matter”. To me, that is just nonsense – and of course no one believes it about animals: if you want the best racehorses or cows producing cream or prize Burmese cats or the fastest racing pigeons, you choose the parents with care. You are of an age to look rather carefully at your parents – many of their qualities you may possess too in greater or lesser measure. Try to build on their strengths and to avoid their weaknesses, but don’t kid yourself that you are a totally different animal.

Fifty-odd years ago, my parents’ belief in education led them to put me in for a scholarship exam to one of the brainiest schools in the country – Winchester College – and, after the first 2 years of almost undiluted misery, I fell in love with the place and I certainly had a good education there. But times have changed. My wife had also been to a boarding school, and we discussed what was best for our 4 children: we decided on plain ordinary maintained schools – 24 pupil-years of primary education (18 in Hatfield) and 28 pupil-years of secondary education (26 at Hatfield School). Neither they nor we have ever had any regrets.

I was a boy at boarding school at Winchester from age 13 to age 18, from 1931 to 1936. The scholarship that I won,

Kenneth Hutton, September 1935

together with 18 other boys (no girls!) in my year, meant that my parents only had to pay fees of £10 per term instead of about £100 per term. The exam was a stiff one. Although Ancient Greek was not compulsory, if like me you had not learned any then you just had to do far better on the other papers; there were only 2 of us who got in who hadn’t done Greek; the other 17 all had. But I had an exceedingly good memory in those days and had been taught the kind of things that mattered – for example in those days William the first 1066, William the second 1087 and so on – I got the top mark of anyone in the History and Geography paper. The other thing I did particularly well at was the Latin Grammar papers. There were two papers in Latin – or were there three? I forget – the translation from Latin to English was difficult and the translation from English to Latin more difficult but Latin Grammar – an extraordinarily complicated subject – was easy to me because all you had to do was remember all the 6 cases of the noun, and which of 3 genders it was, and all the 500 (was it) irregular verbs, and dig into your memory and there it all was. I’ll tell you more about Latin later and my campaign against it; but I fought it because it was bad for other people – it had actually done me a good turn.

The biggest change for me, of course, was being away from home, for 3 months at a stretch, at the other end of the country, among strangers. Of course they weren’t really strangers – it was I who was strange. They were all Southerners, but I spoke with a northern accent saying such awful things as ‘Police COnstable’ instead of ‘Police CUnstable’, so that a boy who disliked me would call out after me “Newcastle Grammar School”. Even in the company of the 70 scholars who wore long black gowns and lived in the original stone buildings built by William of Wykham in 1393 I was the odd man out because of Greek. The others were 7 or 8 together in each Greek form; I was all alone in a non-greek form where everyone else was 2 years older than me.

All of this was, I suppose, an unconscious training to accept being ‘different’ and to hold on to those things I liked and believed in, regardless of what other people did. The equally important and probably more valuable part of my training came mostly later – learning how to cooperate with people and how to take their opinions and wishes into account.

What most of you will regard as the oddest part of my early life was in fact quite common 50 years ago – the absence of girls. Even in the maintained sector of education the sexes were rigidly separated from infancy upwards, with separate entrances for boys and girls inscribed in stone. Later on there developed the odd phenomenon of the Mixed Infant. I had no sisters, a few older nice girl cousins – mostly called Kathleen – but they all lived a long way away, and not until I went to Oxford did I meet any girls. Even then they were few and far between; only 10% of the students in Oxford in 1936 were women and they lived in colleges far away from the men’s colleges. And, in the subject I was studying, Chemistry, out of 64 students only one was a woman: there was so much competition to take her out that I never got a look in.

But life in Oxford provided plenty of other opportunities. Concerts were still few and expensive. Radios were expensive – I didn’t possess one – and not all that much good music was broadcast. So the way to learn music, apart from playing and singing in everything you could join in, was by means of gramophone records. My 5-year-old (but not yet worn out) set of 6 records of Beethoven’s Eroica Symphony came into its own when the Oxford University Gramophone Society was born in the spring of 1938. For 10/- (50p) per term you could borrow a symphony or concerto or other set of records for up to one week. Of course the problem was that the subscriptions of the 30 people only paid for 10 sets of records, so we all had to lend as many as possible records of our own to make sure there were enough records to go round. That was my first major lesson in the difficulties of getting a brand-new venture started, and the enormous value of lots of people co-operating together. What is impossible for one person is easy with 30 and with 240 members as we had after 2½ years it became a real power. After a term I was asked to become ‘President’ and run the society as most of the rest of the committee were not keen on too much organising work. It was enormous fun: although I had no money to spend myself, I could buy any records that I wanted for the society and we were by 1940 the largest lending library in the world, far larger than anything in America. The library still [in 1981] exists and flourishes – we gave it to the University of Oxford.

I think that that made me rapidly grow up, from a shy brain with a good memory who could get fairly high marks in exams, into a real human being dealing with other human beings and coming to terms with economic realities

A choral society, which I joined because it advertised that it would perform Bach’s ‘St John Passion’ which I wanted to sing in, announced at its first meeting that it was £37 in debt and had only 12 members and so it couldn’t continue. I said they must continue and get out of debt … so they made me secretary. More important, as I stood each week at the entrance with the attendance register recording names of members as they arrived, one of the Altos smiled at me; in due course I asked Barbara if she would be willing to be assistant secretary, and then as we enjoyed working together we got married and have enjoyed working together ever since for almost 40 years. The only difference is that, now I have retired, I am Barbara’s Assistant Secretary.

During the War I was required to work as a Research Scientist, first on Local Anaesthetics in Oxford and, later on, in Chemical Industry for I.C.I. on Teesside. I learned not to believe everything I saw in print, not even if it was published by the professor under whom I was working. When I was at I.C.I. I learned an absolutely fascinating technique of instruction and learning which certainly altered my life and which I think is the most valuable single thing that I ever learned. And I learned that chemicals are made because someone wants to buy them at an economic price, rather than because they are theoretically interesting.

I had always wanted to teach, ever since I was 6 or 7 years old, but I had learned to keep it dark because people laughed at the idea, and I had quite enough of being laughed at. But I got an unusual opportunity, during my academic research, of taking a temporary teaching job for a month to fill in for someone who had been called up for the army. Not only did I like it, but – to my surprise – I found that I could keep order. So when a permanent post was going there at the end of the war, I was invited to apply and I accepted.

After 7 years of teaching, very happy years with my children aged 2, 4, 6 and 8, it became clear that a thoroughly dangerous and ambitious man was almost certain to become the next Headmaster. So – unwillingly – I and many others on the staff started looking for other jobs. After one unsuccessful attempt I wrote to a Chief Education Officer with whom I had been in contact on other matters and asked him if he could let me know of any headships likely to become vacant in his county. He asked me to come and see him, which I did. Later he invited himself to a meal with us so that he could judge Barbara and our home. Then he told me that it would be worthwhile keeping my eyes open for some adverts likely to appear in the next month or so, especially one for Hatfield.

This advert was presumably something which I have treasured and I ought with luck to dig it out of a scrap album, buried somewhere in the house so that I can quote it to you. But I’m sorry, I can’t. It was for the Headship of a new Secondary Technical School for 720 boys and girls in a new building, opening in 1953. I put in my application, having written to various ‘referees’ asking permission to use their names as people who would vouch for my character and ability. One of them, still a very good friend said “Yes if you can give me an assurance that you are not a member of the Communist Party because in I.C.I. many of your friends had been.” I was able to give him the assurance that he asked for. (I was known to my pupils as ‘The Red Doctor’ partly because I did not vote Conservative and partly because my Doctorate entitled me to sport a gaudy scarlet gown on Prize Giving Days). I’ve always voted Labour …

The Interviews on 9th January 1953 in Hertford County Hall were for 6 of us, all nice chaps who became good friends chatting together in the long waits whilst the others were interviewed for half an hour each. There was a panel of 6 people interviewing each of us; each of them asked at last one question. The one which floored me was ‘Mr Hutton, have you any experience of administration?’ I reviewed rapidly in my mind being the “President” of the OU Gramophone Society, Secretary to the Governors of King Alfred’s Training College for Teachers, and especially master-in-charge of Winchester College (pupils) Photographic Society, and decided that the only honest answer was ‘No, Sir’. So I thought that ruled me out, and my personal vote went for the very nice Principal of Welwyn Garden City Evening Institute, and thought it had all been very interesting. I was glad it was all over and perhaps I would be able to sleep that night instead of shivering all night in a fit of nerves. Then they asked ME to come back into the interviewing room and offered me the job. I was staggered!

Two or three years later when it was safe to say so, and there was no longer any serious danger of me being dismissed for incompetence, I used to say that I had 4 qualifications for the job:

1. Although I know nothing about 11-year-olds, my first 120 pupils would be all aged 11 years old.

2. Up to half of my pupils would be girls, and I know nothing about girls. My only daughter was 4, I had never taught girls and I knew little enough about women.

3. I knew practically nothing about the national system of education. I had been educated and had taught only in the fee-paying sector. But my two eldest sons were in a maintained primary school in Hampshire.

4. And finally of course, I had never been in charge of anyone or anything else in the education sector, not even in charge of a chemistry department, let alone a science department, and of course I knew nothing about administration or about being a headmaster.

I had everything to learn. Fortunately a large number of people were willing to help me to learn, and were patient and forgiving when I made mistakes. To start with there were two of the panel of interviewers:

One was the Chairman Mr John McKnight, head of administration of the School Broadcasting Council of the BBC , and who was the first Chairman of Governors of Hatfield School and remained almost uninterruptedly for 20 years. (I hope to be able to say “I went to see him yesterday”) It was he who had the idea of having “Sixth Form Lecturers” with time for informal lunch and questions, rather than just a pronouncement from on high. I feel very honoured at being on the list of varied and interesting people who have preceded me, including Lord Ashby, Sir Adrian Boult, Professor Gordon Manley, Mrs Lena Jeger MP, Dilys Powell the film critic and so on …

A good Chairman of Governors is the best asset a Headmaster can possibly have. He must be 100% for the School, and indeed 100% for the Head but NOT necessarily in favour of the particular decisions which you are about to make, and willing to point out as forcibly as may be necessary to convince when he thinks you are in the wrong. I remember vividly receiving back from him a motley sheaf of papers, which I was intending to send out to new parents, with the curt comment ‘This is a mess’ (it was) and the brilliant new thought ‘It’s time you went into print’ and we did with “Hatfield School – a guide for parents 1962”.

The other vitally significant person was “The Boss”, the County Education Officer, John Newsom, later Sir John Newsom, who was in charge of the very best county educational service in the whole country at the time. He had Conservative councillors proud of the fact that they spent more on education than anyone else, and even willing to send their own daughters to county schools, though hardly ever – I think – their sons (who had to go to fee-paying Schools).

John Newsom had worked harder than anyone else for equality of status and facilities between secondary modern schools and grammar or technical schools, and in Hertfordshire had succeeded very well. In the rest of the country it was very different. The Newsom Report “Half our Future” published 10 years later in August 1963 showed just how unfair a deal the Secondary Modern Schools had had, and especially how they were plagued by a staff turnover about 3 times as fast as would be the case in a healthy school. (My calculation showed that, on this criterion, Hatfield School was healthy) The very first quotation, facing Chapter 1 of the Newsom Report was as follows: “A boy who had just left school was asked by his former headmaster what he thought of the new buildings. ‘It could all be marble, sir’ he replied, ‘but it would still be a bloody school’.

John Newsom was forthright with Heads, taking you to task privately when you had done wrong, and even more important saying ‘well done’ promptly when you deserved it, and probably in public. A nice example of both processes was when Mr Duncan Sandys, then Minister for Housing, now Lord Sandys, had opened a Shopping Centre and Hall-cum-Church for the Roe Green area of Hatfield New Town just opposite our back door. For those of you too young to know, a “New Town” means a sea of mud, no footpaths, everyone going about in gum-boots, and no shops for miles. So it really was splendid when after 18 months in our house we at last got a footpath, and just across the road 5 shops and a paved forecourt. Splendid until the Northeast wind blew all the litter off the shopping parade directly into our garden because no-one had provided litter-baskets.

I spent the entire evening clearing up the mess, with yard broom, wheelbarrow and finally with a bonfire. Then I wrote letters to everyone I could think of – the 4 local newspapers for a start, St Albans, Welwyn Garden, Hatfield, Potters Bar – the 3 public authorities the Hatfield RDC, the WGC and Hatfield New Town Development Corporation, the Herts County Council etc. telling them what I had done, asking for their help in providing litter baskets and emptying them; and copies to the local shopkeepers asking them to please sweep each day outside their own shop.

From the County Education Officer.

Dear Headmaster,

The Clerk to the County Council has drawn my attention to some letters written by you to local newspapers, on county council notepaper, complaining about some lack of action on their part.

I must remind you that this is no way for one servant of the County Council to address another; moreover you were acting in your capacity as a private citizen, and therefore should not have used official headed notepaper.

I must ask for your written assurance that this will never happen again.

Yours faithfully,

JH Newsom

County Education Officer

copy to the Clerk to the County Council.

Attached to this typewritten letter was a handwritten one which said “Dear Kenneth, Here is your official rocket which you richly deserve. But by jove you have stirred up the slumbering bureaucracy! Well done. Yours ever, John”

Similarly when we decided to build our own swimming pool, John Newsom provided both immediate encouragement and hard practical advice. “The next meeting of the Education Committee is on January 7th. Ten days before that you will have to provide 12 copies of the Architect’s drawings, typed copies of the Engineer’s report and of an accountant’s assessment – and so on”

But I am moving on too fast. We needed a curriculum, a staff, a building, and books and apparatus, – and of course some pupils. There were about 8 months to go. I was to be appointed from April 1st so that I had time and energy to tackle all these multifarious tasks. So I gave in my notice to my present head, Walter Oakshott, now Sir Walter or is he indeed Lord Oakshott – time does make people eminent, even me as a Sixth Form Lecturer! Walter gave me some excellent advice “Try to distinguish between the very many occasions when all that is needed is a decision, (no matter what that decision is) and the few important occasions when what matters is that you should make the correct decision.” He was one of the most charming of men, who spent hours agonising about unimportant decisions like what day should be an extra half-holiday! (He did in fact give a half-holiday in honour of my second son David’s birth in 1946 and my youngest son Hugh’s birth in 1950. Mary, born in 1948, was a girl and did not count!)

It is difficult to realise that our curriculum and timetable were at that moment just blank sheets of paper. When should school start, when should it end, when should there be breaks, how many periods should there be in a day, and WHAT SUBJECTS should be taught and for how many periods? Blank sheets of paper – and 120 eleven-year-olds arriving in September to be taught by an unknown number of at present unnamed teachers. A daunting prospect, but I was only 34, in excellent health, happily married and full of optimism.

I did know that there were such things as Her Majesty’s Inspectors of Schools because I had been on 3 courses run by them, and 2 of my pupils had fathers who were HMI. But it never occurred to me to ask HMI! It was a practical problem to solve.

What sort of pupils did I expect? The authority provided the answer – Parents of pupils will be able in 1953 to put as one of their choices for the 11+ exam, Hatfield Secondary Technical School if they live in the divisions of Mid Herts, St Albans, East Herts North Herts or South Herts. This was in fact a most generous opportunity for a new school: although situated in the Mid Herts Division, it was not just competing against one well established Grammar School at Welwyn Garden City for the brightest 25% of the child population. Parents from further afield could, if they wished, ask for their children to be considered. We had to show that we were offering something different, and better in its own way than the existing schools. It was almost impossible that we could convince anyone that we would do better if we offered exactly the same.

I personally had to make some revolutionary adjustments to my own thinking. Of the pupils I had been teaching at Winchester, one half were in the brightest 1% of the population and virtually every one was clearly in the top 25%. Even if the new Hatfield Secondary Technical School got its fair share of potential university students – and that was extremely improbable – they would form an absolutely tiny proportion of the pupils I taught, instead of being the normal folk sitting in front of me in class. So I managed to squeeze two visits to ‘ordinary’ schools to see what ‘ordinary’ pupils were like and also get copies of their timetables. One was a Secondary Technical School at Newport (Isle of Wight) and the other was Watford Boy’s Grammar School whose head, the famous Harry Ree DSO, MC, French Resistance etc had been helping me with my researches into the intelligence of pupils.

Hatfield School, September 1953, some New Entrants & incomplete building

The decisions on what subjects to teach were, I suppose, arrived at more or less like this:- Our building (that was at that moment being built) was designed as a secondary technical school and so it had got a woodwork room, a metalwork room, an engineering machine shop, a cookery room, a needlework room, art room, 2 craft rooms, 4 laboratories, gymnasium, Hall and ordinary classrooms. So quite clearly the opportunity was there to teach practical subjects. It is interesting to contrast this with other schools at the time. The best known of the other schools in our catchment was called “Queen Elizabeth’s Barnet” founded in 1558 or so. Not only was there no woodwork room in the building, but the headmaster resolutely refused any attempts by the County Education Committee to give him one on the grounds that woodwork was no part of a gentleman’s education and therefore would not be taught in his boys grammar school.

Where I had been teaching, at Winchester, there was of course no question of cookery or needlework, but boys could go in their spare time to learn woodwork from an instructor or art from the art master or music from a whole variety of teachers who didn’t quite count as full members of staff. I myself had never learned any art or woodwork, still less metalwork or cookery, though I had had music lessons from the age of 6. So here was an opportunity to ensure that all of our pupils learned some skill with their hands, by having practical subjects in the curriculum of 11-year-olds, because our facilities allowed us to do so.

One of the most vexed questions in the whole curriculum is that of foreign languages. It was far more vexed in those days when the Dead Languages were still King and Queen! A very large proportion of the Top People in the country had been to the University of Oxford or the University of Cambridge. Most of the people who wanted their sons to be Top People wanted them to go to Oxford or Cambridge. Without Latin you could NOT go! So, for the sake of the absolutely tiny number of people entering ‘Oxbridge’ each year, I suppose about 2000 people from the whole country, the curriculum of one quarter of the population i.e. about 100 thousand boys and girls entering grammar schools each year, ALL had to learn Latin.

When I say ALL you can be quite sure that I must be exaggerating because there are no absolute rules in British education. There may have been some tiny grammar school where they started Latin at age 12, not at age 11. (I had to start Latin at age 8½ – that was called a general education) But it is certainly true to say that about 50 times as many people were taught Latin as actually needed it to get into Oxbridge.

It is not even quite true to say that you couldn’t get in without Latin. Greek would do so long as it was Classical Greek, a language that could not be understood in present-day Greece. Classical Persian would do equally well, or Classical Arabic or Sanskrit or Classical Chinese. But you had to pass an exam in a DEAD language as well as a modern language to enter either Oxford or Cambridge.

We decided NOT to teach Latin! I’m not quite sure who ‘we’ were. My guess is that I wrote to John McKnight, the Chairman of Governors, and he probably telephoned John Newsom the County Education Officer, and he may well have had a word with the HMI for the county. I’m sure that at one stage there was a statement in the local press by John Newsom saying ‘No Latin’ but I can’t remember when that was.

What about Foreign Languages, of which French was the standard choice in 99% of schools? Or could we do without a foreign language? It is fascinating to remember that this was a real possibility – we had no French Teacher on the payroll who would have to be given redundancy pay or persuaded to teach music or history or woodwork! Well of course we did decide to have a foreign language, but it did not have to be French. Why did so few schools start with anything else? French is in fact difficult for English speakers because its rhythm is totally different, there are no gaps between words, no stress on any one syllable in a word and it is normally spoken very fast and with no clear articulation. Few English people of my generation, who were brought up on French as if it were a ‘dead’ language with the emphasis on irregular verbs, one mark off for each spelling mistake, and those accursed genders, ever managed to understand a French man speaking to him, let alone a French woman!

By contrast, Spanish and Italian were said to be phonetically spelt and the words as easy to learn as in French; Russian might be important , but was clearly much more difficult, so what about German? Here I had plenty of good advice to hand, with two close friends who taught modern languages on the same staff as me. They pointed out that there were about as many graduates in German each year as in French, but only about one tenth of the number of teaching posts. So it was far easier to find a really good teacher of German than one of French.

I must be honest and also declare my own personal interest. I had been taught German by a quite splendid teacher, by the direct method with no words of English spoken in class so that you had to think in German, and I had found that I could make myself understood in Austria or Germany as well as understanding much of what was said. And German is the language of much of the best music – Schumann, Schubert, Beethoven, Brahms, Bach as well as the richest collection of folk songs. German it was.

You see, in those days there was no question of pupils having learned any French in primary schools, so the only real obstacle was that children of parents who moved jobs out of the area might suffer because they were ignorant of French when they arrived at their new school. I think that that did in fact deter a number of the more ambitious, mobile, parents from sending their children to Hatfield School.

Well, by now enough decisions had been made for an Advertisement for Teaching Staff to be inserted in the Times Educational Supplement, and as term neared its end replies began to come in. The first meeting of the Governors was fixed for 1st April 1953; we were going to move from Winchester to Hatfield about 2 weeks later, and in the mean time I was very busy with all the usual end of term rush in my normal job of Teaching Chemistry and a bit of Physics. A pupil who had been taking a scholarship exam at Oxford for chemistry brought his theoretical papers to show me in my classroom, and one of the questions caught my eye: “Why, if one drop of water is added to a mixture of powdered silver nitrate and powdered magnesium metal does it give a flame?” I said,”Well I never knew that but I suppose you can suggest why”. I’m not sure if he did explain it, but anyway I said “come on, let’s try it”.

With the very tiny amount of silver nitrate powder remaining at the bottom of the bottle and about a salt spoon full of magnesium, I added a drop of water. The next thing I knew was a burning sensation in my eyes and the most acute pain I’ve ever known. That lasted from 11am till 7pm in spite, eventually, of morphine. Then 300 pieces of metallic silver were removed from my eyes and I was bandaged up in the dark in hospital for the next 3 days. Then came the moment when they removed the bandages from my eyes – and I could see again.

The Hutton family at home, c.1962

Meanwhile, with 4 young children aged 9, 6, 4 & 2, Barbara had to run the house, visit me in hospital, make contact with Hertfordshire to cancel the Governor’s meeting and send off notices to five hundred and fifty applicants for teaching posts (!) to say that ‘unfortunately interviews will have to be delayed’. All this as well as corresponding with an architect about the house he was designing for us, and preparing to move, temporarily, into a tiny house in 2 weeks time! Fortunately she coped. But let no one doubt the magnitude of the help that a wife can give to her husband – or indeed vice versa.

After that, most of the important information is on the record, in the file of Headmasters Reports to the Governors, and of minutes of the Governors meetings, in two enormous Log Books which were really outsize Scrap Albums, and bound volumes of the School Magazine. In fact, if I were to try to tell you from memory I would probably get it WRONG. I was trying to think how we got our name ‘Hatfield School’ and when; I couldn’t remember. But I have located the minutes of the first two meetings of the Governors: On Tuesday 30th December 1952 and 22nd April 1953. They give the answer.

The first meeting (30th December 1952) has two main items of interest:

“Minute 6 The purpose of the School. The Chairman (Mr John McKnight) asked the County Education Officer to outline what he thought was the main function of this school. Mr Newsom said that was really something that would grow, dependant on the personality of the headmaster, but that he wished the school to be part of the selective provision of education in the middle of the county. He insisted that it should have high academic standards, which meant that some of the children with the best ability from the area should be encouraged to go there so that a sixth form could be developed. It was the job of the school to attract them. There was discussion on this and the governors asked that publicity be given to the aims of the school so that parents in the area would know of it when they came to choose the secondary school for their children.”

Minute 8 of that same meeting is headed:

“Name of the School. The Governors thought that there would be prejudice in the minds of the parents if the name continued to be Hatfield Secondary Technical School, the history of secondary technical education on the whole compared unfavourably in the past with that of Secondary Grammar Schools. It would be unfortunate if this School had that initial disadvantage. It was agreed that the name of the School should be considered by the Governors at the next meeting.”

Minute 12 of the next Governors’ meeting, Tuesday 22nd April 1953 reads:

“ Name of the School. The Governors gave careful consideration to the various proposals and made the following recommendation to the Education Committee.

Recommendation. That the new school be known as “Hatfield School”.

Interestingly I turned up recently an early duplicate book with a carbon copy dated 13th June 1953 (i.e. 7 weeks later) ordering 4 reams of headed paper with the official title “Hatfield School, Roe Green Lane, Hatfield, Herts.”

Hatfield Technical College and Hatfielld School, 1954

By now, I have told you about how a place called Hatfield School came into existence, and how a person called Kenneth Hutton came to be Head of it. The next 13 years were by far the most interesting, important and enjoyable in my whole life. Whatever can be said against the job of head of a school, no one will deny that it is important to a very large number of people – especially to pupils, but also their parents, to the local community, maybe also to the educational system as a whole. And a Head can do nothing by himself, he has to work through his colleagues on the staff. So it is the teachers who are all important. I am delighted to be still in touch with a considerable number of my ex-colleagues and to see quite a few of them still serving Hatfield School.

I must remind you – as I must remind myself – that in 1953 Hatfield School was in a different place, in different buildings, a different kind of school not yet comprehensive, and of course it was also a very different world. We were far poorer in material possessions – only one teacher on the staff had a car; we came by bus or bicycle or walked – but we were optimistic that the world was becoming a better place, less unjust, kinder, less inefficient, and that if we worked hard enough and used our brains, we would play our part in making the world a better place and we would have an interesting and enjoyable life in doing so. I still believe that and I hope that you do too.

We were a tiny school – only 120 eleven-year-old pupils. Generously the County Education Committee allowed us 9 staff in that first year so that we didn’t have to teach too many subjects and skills that we were ignorant of. We had to be willing to try and to learn as we went along. The young lady P.E. Teacher taught the boys as well as the girls – and loved it. The History master also taught music, playing tunes on the piano with one finger. And I, who had only learned a tiny amount of biology at school, was teaching that as well as physics and chemistry – with a lot of coaching beforehand from Mrs Fitzpatrick.

Molly Fitzpatrick, Kenneth Hutton, Bill Pidcock, September 1953

We had decided that we would teach about human reproduction to 11-year-olds in the natural course of their science lessons, and based our scheme on broadcast lessons and pamphlets produced by the BBC. Being a new school, we had a very large number of visitors of all kinds (over 2000 in the first year), and one party of 17 student-teachers came in to the lesson which was the first one I’d ever given in my life on human reproduction. Towards the end of the double period, in questions from pupils, a boy called peter Bird said “Sir, a human mother fertilises her own egg doesn’t she?” So I had to explain again the part played by the human father, to be faced with the reply “But I’ve never seen my Father do that!” (He had just acquired a baby sister and evidently the explanation at home was different from that at school, even though we had sent a letter home to parents explaining what we were going to do).

After the end of that lesson, one of the students said to me “Did you know you had 23 questions?” To which my reply was – “I had no idea; I was far too busy answering them”. That reminds me that what I am really looking forward to doing is answering questions afterwards. I’ll then know what you really want to know, instead of trying to guess what – out of 13 hectic and fascinating years – will be of the greatest interest and importance to you.

I have found that one absolutely essential skill to try to acquire is that of finding out what the other chap is thinking. I am still bad at it – I haven’t any intuition. So I have to do my best in 2 ways. The first is to think “If I, Kenneth Hutton, was still being lectured to after 40 whole minutes like this, what would I be thinking? – and then to add the important qualification “but they are NOT Kenneth Hutton, they are 45 years younger and different in a whole lot of ways.” I wonder how many of you have got as bored as I used to get in lectures? Who has tried today to remember all 54 counties of England and Wales, or all 50 of the United States, or all 104 Chemical Elements, or as many independent countries of the World as there are?

The other way to find out is actually to ASK the other chap what he or she is thinking. The snag here is that it will only work if they are sufficiently unafraid of you to tell you, however unpalatable the answer may be. (Mr Slaney – when do you want me to stop?) Actually this seems often to have worked because I recently came across a carbon copy of a reference I had written for a pupil who was intending to be a teacher, and I said how, when he was a prefect, he had been sufficiently brave and tactful to be able to tell me that he thought I was in the wrong about a disciplinary problem, and to convince me!

It is fascinating how many ideas come up, from pupils and from staff, if new ideas are encouraged. One of my initial staff – now I think the highest paid teacher (rightly) in Britain – had an enormous number of new ideas. In fact, very many of the good ideas that developed in Hatfield School in my time were his ideas. One fairly novel one (25 years ago) was having a School Council, so that pupils could discuss things that mattered to them and have the joint secretaries bring the fruit of their discussions to me. The very first thing they wanted was an extra drinking fountain, and which wasn’t blocked up. A remarkably ‘obvious’ point when you come to think about it, yet no-one on the staff had thought of it, and no pupil had said it.

I always reckon that “obvious” is a dangerous word. What is obvious to me is NOT obvious to you. And what is obvious to YOU is not obvious to me! It is not what I write that matters but what you read. It doesn’t matter what I say, but it is what you hear which is vital.

I have often been delighted when an ex-pupil has remembered with approval something that I said. Ann Richards, now in Australia, reminded me “Dr Hutton always told us that the one safe place for a letter you have written was in a stamped and addressed envelope inside a pillar box”. More significantly, last year Sally Miles reminded me that I had taught her never to believe what anyone taught her, not even what I taught her, without testing for the possibility that I might be mistaken or misleading.

Coming back to the problem of turning bright ideas into reality – how can you do it? It requires CONSTRUCTIVE thought, and that is rarer than one would like it to be. Television and newspapers are full of things going wrong: good news is no news! The reason is that building anything up takes time and that is therefore not news. But destroying something can often be done in a moment with high explosive or cuts in public spending.

First you need to think carefully what it is that you really want. Is it absolutely essential to marry someone with a first class degree and a passion for playing piano duets and cycling down hill at 30 miles an hour – as I once thought. Or were the really vital ingredients an interest in things of the mind, a delight in music and in exploring the world in the open air, coupled with the unusual ability to go on being fond of me? Must you really have a fully-equipped Sixth Form Common Room by next week without you yourself doing a hand’s turn of work – or are you willing to do a hell of a lot of work so that your younger brother just starting in the 5th form might have a week or two in some sort of common room before he leaves the school? (Both these examples are, of course, from real life!)

Once you have reduced your dreams to more moderate dimensions, and decided on a vast dose of PATIENCE, you need to cultivate your talents of persuasiveness. Who do you need to get on your side to help you, especially to advise you on what the necessary steps are, and in what order to take them? And what are the key points that have to be successful in order that the whole project shall not fail? It is said of the composer Bach – the great Johann Sebastian – that his recipe for success was 1% inspiration and 99% perspiration (but I rather doubt if it sounds quite so well in German)

I think that I have talked quite long enough. I’d like the rest of my time to be spent answering questions. But I don’t want to end without expressing the fervent hope that you all want to do your best to put the world to rights (NOT merely to make pots of money or to have an easy life) and I hope too that you feel optimistic enough to think you are likely to have some success. I am sure that if you want to, you will.

NB Have you checked recently the other HS Pages/Posts listed and hotlinked in the list at the top right of this page ? The titles don’t say everything, and new edits and new Posts are being added often.

Add your comment about this page

I transferred to Hatfield School from a secondary modern school, where I had only been able to take two ‘O’ levels, in English language and biology. I wanted a career in science, so I wrote to Dr Hutton and explained what I wanted to do. He interviewed me and made me take an intelligence test. I don’t know what the results of that were, but he offered me a place. I duly passed a clutch of ‘O’ and the required ‘A’ levels over the next three years. This enabled me to train as a biomedical scientist, a career that lasted for 40 years. I have been forever grateful to Dr Hutton for listening to me, and giving me a chance, which at that time seemed a remote possibility. It also gave me an amazing social life, with the dances, school plays etc. He was a real ‘one off’, and a real influence in the outcome of my life.

I was absolutely terrified of Dr Hutton.

This reads like the Dr Hutton I remember.

“Try it and see”, the mantra in the chemistry lab.

But I used sodium chlorate and ground up charcoal to get myself into A&E at St Albans General Hospital.

Who am I ? See image “some New Entrants & incomplete building”, second row (sitting on chairs), third in from the right.